Exploring New Places: Wildlife of South Carolina's Atlantic Coast

Having grown up not too far from the breath-taking rugged coast of Central California, I will be forever loyal to the west. From the rocky, fog-enshrouded coast of Washington's Olympic Peninsula and the deserted beaches of the Redwood Coast, to the turquoise inlets of the Monterey Bay, the mild, Garibaldi-spangled waters of San Diego, even the tropical sands of Hawaii, I have swum, snorkled, camped, birded, hiked, rode horseback, collected shells, explored the magical worlds of tide pools, and wandered blissfully - usually barefoot - up and down miles and miles of western beaches. The Pacific is in my blood.

Only recently, I had the privilege of visiting South Carolina and experiencing my first taste (quite literally) of the Atlantic. Slipping off my sandals and wading out into the sea for a swim, I was pleasantly surprised by the comfortable temperature of the water. I'm not sure what I was expecting, but perfectly warm water was not it!

You must remember, the beaches where I come from are nearly always cold. Frigidly so. Just as winter breaks, "June Gloom" settles in over the coast of Central California and days are often foggy or cloudy. Thanks to the Pacific Ocean's clockwise currents which bring northern waters to our shores, the water temperature hovers around the mid-fifties (in degrees Fahrenheit) year-round. Sunny days come most frequently in the fall, but are often accompanied by a strong wind off the Pacific, acting like a giant evaporative cooler. Warm clothing is nearly always required. Even at the height of summer, as temperatures soar past 100 degrees in the Central Valley, we head to the beach to cool off and know to bring along our sweaters!

What a treat it was, then, to visit the sunny Atlantic in August, don bathing attire, lay out our beach towels and run headlong into water that was the ideal temperature: not too cold that one must keep moving to stay warm (you know the type of swimming water I'm referring too), but still cool enough to be refreshing in the oppressive heat and humidity of an August afternoon in the South.

Being on the opposite side of our great continent, we have the clockwise Atlantic current, known as the Gulf Stream, to thank for pleasant swimming conditions as warm water from tropical seas is conveyed northward along the temperate coastline.

Of course, bathers and other beach-goers are far from the only visitors that appreciate warm Atlantic waters and pristine sandy beaches. Long before sky scrapers, hotels and seaside resorts were built up and down the coast, wildlife laid claim to these waters and strands.

On dark summer nights from May through August, loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) haul themselves out of the sea, across beaches and into the relative safety of sand dunes. In the dunes, above the reach of high tides, female loggerheads dig nests in which they lay an average of 120 eggs (which are very similar in appearance to ping pong balls). Once the eggs are laid, she buries them in the sand before returning to the ocean. And that is the extent of her maternal duties. The eggs are left to incubate in their sandy nests for 60 days; hatching takes places from July to October.

This year, according to the Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring System, 41 loggerhead nests have been laid at South Carolina's Huntington Beach State Park.

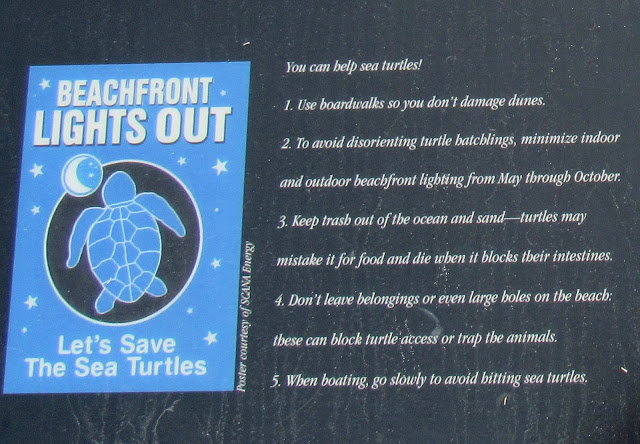

Loggerhead sea turtles have been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act since the 1970's. In addition to marine pollution, fishing and hunting, some of the leading causes in the decline of the loggerhead sea turtle are loss of nesting habitat, excessive nest predation, and hatchling disorientation due to the presence of artificial lights on otherwise dark beaches.

To guard against excessive nest predation and accidental (or intentional) disturbance of nests by human beach-goers, programs are in place that closely monitor beaches during the nesting season and protect active nests with wire cages and informational signs. The cages allow newly-hatched sea turtles to pass through the wire mesh, but prevent the nest from being dug up or otherwise tampered with by predators or people.

Newly hatched sea turtles are drawn to the sea by the reflection of the moon and stars on the water (which sounds terribly romantic, doesn't it?) - or, specifically, the blue and green wavelengths of light reflected on the water from celestial bodies. If man-made sources of light - from beachfront homes, streetlights, gas stations and city lights in general - are brighter than the light reflecting on the water, hatchlings are attracted to the wrong lights. Man-made lights lead them in the wrong direction and the newly-hatched sea turtles become disoriented. As artificial lights draw hatchlings away from the ocean, the baby turtles expend valuable energy crawling in the wrong direction, are exposed to predators for a longer period of time, and risk desiccation. Even beach-goers with flashlights or bonfires can disorient sea turtle hatchlings.

Be aware that you are visiting sea turtles' nurseries: tread carefully, be considerate and minimize your use of beachfront lighting from May through October. Visit the Sea Turtle Conservancy for more information and suggestions on how to help sea turtles.

Of course, sea turtles are not the Atlantic Coast's only type of wildlife that depends on undisturbed stretches of sandy beach and dunes for reproductive success. A number of bird species nest here as well.

While a handful of species nest on South Carolina's beaches, even more pass through during migration and spend the winter along its temperate waters. Let birds be birds: don't disturb shorebirds that are resting or feeding, as both of these activities are critical to the survival of migratory and overwintering birds. Keep your dogs leashed and don't allow kids to chase birds! While your next snack is only a walk to the fridge away... many of these shorebirds have traveled hundreds or even thousands of miles and must work hard to forage for enough calories to replace those lost during migration or while tending a nest.

For more information on South Carolina's beach nesting birds, check out this reference guide.

|

| My first experience of an Atlantic beach, at South Carolina's beautiful Huntington Beach State Park. |

Only recently, I had the privilege of visiting South Carolina and experiencing my first taste (quite literally) of the Atlantic. Slipping off my sandals and wading out into the sea for a swim, I was pleasantly surprised by the comfortable temperature of the water. I'm not sure what I was expecting, but perfectly warm water was not it!

You must remember, the beaches where I come from are nearly always cold. Frigidly so. Just as winter breaks, "June Gloom" settles in over the coast of Central California and days are often foggy or cloudy. Thanks to the Pacific Ocean's clockwise currents which bring northern waters to our shores, the water temperature hovers around the mid-fifties (in degrees Fahrenheit) year-round. Sunny days come most frequently in the fall, but are often accompanied by a strong wind off the Pacific, acting like a giant evaporative cooler. Warm clothing is nearly always required. Even at the height of summer, as temperatures soar past 100 degrees in the Central Valley, we head to the beach to cool off and know to bring along our sweaters!

What a treat it was, then, to visit the sunny Atlantic in August, don bathing attire, lay out our beach towels and run headlong into water that was the ideal temperature: not too cold that one must keep moving to stay warm (you know the type of swimming water I'm referring too), but still cool enough to be refreshing in the oppressive heat and humidity of an August afternoon in the South.

|

| Huntington Beach State Park, South Carolina (north of the crowds) |

Being on the opposite side of our great continent, we have the clockwise Atlantic current, known as the Gulf Stream, to thank for pleasant swimming conditions as warm water from tropical seas is conveyed northward along the temperate coastline.

Of course, bathers and other beach-goers are far from the only visitors that appreciate warm Atlantic waters and pristine sandy beaches. Long before sky scrapers, hotels and seaside resorts were built up and down the coast, wildlife laid claim to these waters and strands.

|

| Dunes at Huntington Beach State Park |

On dark summer nights from May through August, loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) haul themselves out of the sea, across beaches and into the relative safety of sand dunes. In the dunes, above the reach of high tides, female loggerheads dig nests in which they lay an average of 120 eggs (which are very similar in appearance to ping pong balls). Once the eggs are laid, she buries them in the sand before returning to the ocean. And that is the extent of her maternal duties. The eggs are left to incubate in their sandy nests for 60 days; hatching takes places from July to October.

This year, according to the Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring System, 41 loggerhead nests have been laid at South Carolina's Huntington Beach State Park.

Loggerhead sea turtles have been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act since the 1970's. In addition to marine pollution, fishing and hunting, some of the leading causes in the decline of the loggerhead sea turtle are loss of nesting habitat, excessive nest predation, and hatchling disorientation due to the presence of artificial lights on otherwise dark beaches.

To guard against excessive nest predation and accidental (or intentional) disturbance of nests by human beach-goers, programs are in place that closely monitor beaches during the nesting season and protect active nests with wire cages and informational signs. The cages allow newly-hatched sea turtles to pass through the wire mesh, but prevent the nest from being dug up or otherwise tampered with by predators or people.

|

| A protective cage surrounding a sea turtle nest, with a sign that reads: "Loggerhead turtle nesting area. Eggs, hatchlings, adults and carcasses are protected by federal and state laws." |

Newly hatched sea turtles are drawn to the sea by the reflection of the moon and stars on the water (which sounds terribly romantic, doesn't it?) - or, specifically, the blue and green wavelengths of light reflected on the water from celestial bodies. If man-made sources of light - from beachfront homes, streetlights, gas stations and city lights in general - are brighter than the light reflecting on the water, hatchlings are attracted to the wrong lights. Man-made lights lead them in the wrong direction and the newly-hatched sea turtles become disoriented. As artificial lights draw hatchlings away from the ocean, the baby turtles expend valuable energy crawling in the wrong direction, are exposed to predators for a longer period of time, and risk desiccation. Even beach-goers with flashlights or bonfires can disorient sea turtle hatchlings.

Be aware that you are visiting sea turtles' nurseries: tread carefully, be considerate and minimize your use of beachfront lighting from May through October. Visit the Sea Turtle Conservancy for more information and suggestions on how to help sea turtles.

Of course, sea turtles are not the Atlantic Coast's only type of wildlife that depends on undisturbed stretches of sandy beach and dunes for reproductive success. A number of bird species nest here as well.

Shorebirds and seabirds, like sandpipers, plovers, gulls, terns and skimmers, nest on the ground, often laying their eggs in little more than a slight indentation in the sand. While gulls, terns and skimmers nest in large colonies not likely to be missed, oystercatchers and plovers, like the Wilson's Plover which is listed as threatened in South Carolina, rely on camouflage for protection. As a result, the eggs and chicks are difficult to see and vulnerable to unintentional disturbance. Respect posted signs and roped-off sections of beach and dunes by staying out of known nesting areas.

While a handful of species nest on South Carolina's beaches, even more pass through during migration and spend the winter along its temperate waters. Let birds be birds: don't disturb shorebirds that are resting or feeding, as both of these activities are critical to the survival of migratory and overwintering birds. Keep your dogs leashed and don't allow kids to chase birds! While your next snack is only a walk to the fridge away... many of these shorebirds have traveled hundreds or even thousands of miles and must work hard to forage for enough calories to replace those lost during migration or while tending a nest.

For more information on South Carolina's beach nesting birds, check out this reference guide.

|

| Laughing Gull |

Comments

Post a Comment